↧

Sartorial synaesthesia

↧

Golden Shears 2013

The Golden Shears was held last night – the closest thing we get to a tailoring competition.

It’s not really a tailoring competition, in many respects. Everyone makes to a standard size (40 chest, 36 waist) to a fit a mannequin, so bespoke cutting isn’t really tested. Some of the competitors from the fashion schools make the pieces with very little hand work, so the tailoring isn’t universally strong. And half the points are awarded by celebrity judges – last night, Joanna Lumley, Raymond Blanc and others.

No, it’s definitely more fashion, and even then you could ask what most of the judges know about fashion. Most of the mainstream coverage focused on the fact that the winners were all girls, but then girls have won the last three times in a row – there are simply more of them studying fashion and apprenticing to be coatmakers.

I was a little surprised that women’s outfits didn’t dominate the awards (only the rising star award was a woman’s piece, far right, winner far left), for the standard block clearly favours the female models. Their pieces all fitted well, whereas the male models barely had a 38 chest between them, and so always looked swamped in their size 40s.

All that being said, it was a charming evening, as ever hovering somewhere between school prize-giving and college catwalk. You can’t help but smile when each apprentice is beaming from ear to ear, revelling in the attention on their hard secluded labour.

↧

↧

Embroidered velvet jacket: Hawthorne & Heaney

Following my first project with Claire Barrett, who founded embroidery company Hawthorne & Heaney last year, this was a follow-up to decorate the lapel of my Timothy Everest smoking jacket.

I wasn’t entirely sure whether I liked the look of the embroidered suit cuff last time round, but the work sits much more naturally with velvet than worsted and I think the results here were stunning.

Inspired by a design of Claire’s that I had seen, our motif comprised two Hawthorn branches (suitably enough), one curving up towards the peaked lapel, the other following the line of the collar.

The work was more complicated than last time, because it was raised and because it involved gilt. The pattern is created by snipping the right length of gilt, looping the needle through the middle of it (like a chopstick through penne) and securing it by sewing through the grosgrain facing.

We went for an antique gilt rather than normal yellow gold as it echoed the tone of the brown velvet in the jacket. You can see the process below.

|

| The gut-reaching bit: opening up the lapel |

|

| The design is drawn on |

|

| The hawthorne design |

|

| Sewing around the design |

|

| Padding laid on for the Hawthorn leaves |

|

| Thread the pasta |

|

| The finished result |

|

| The range of gilt work available |

↧

Permanent Style in Free & Easy magazine

This column in Japanese magazine Free & Easy is the result of the photo shoot I posted about before Christmas. I have no idea what the Japanese text says, but hopefully it faithfully reports my opinions on shoes and shoe collecting, and describes the shoes pictured – from Cleverley, Gaziano & Girling and Edward Green.

The magazine itself, a shoe special, is a wondrous thing. So many shoes; so much information. There are several obvious errors, at least in the English: Leffot in New York is called ‘Effot’ and the John Lobb feature includes a section called Closing which is actually lasting.

But you can’t knock the volume and depth of information, with step-by-step profiles on Alden, Foster & Son, Lobb, Tricker’s and others, as well as pages of catalogue-type listings.

But you can’t knock the volume and depth of information, with step-by-step profiles on Alden, Foster & Son, Lobb, Tricker’s and others, as well as pages of catalogue-type listings.

↧

Permanent Style x La Portegna

I’ve always loved really soft leathers and suedes – particularly in jackets, but also in slippers and slip-ons. For most men (and I pass no judgment on the rest) slippers are the only leather item they will ever wear against their skin. The only time they will feel that buttery hide against their own. And yet there are very few high-end leather slippers out there.

Most leather slippers are made with low-quality hides, often mid-cuts of the skin that are then coated and printed with a grain to hide the lack of natural surface. Or they are thin pieces wrapped around a foam or cardboard lining.

La Portegna is a small Spanish company with a rather different philosophy. They started out making simple leather travel slippers, made from just two pieces of leather – the sole and the vamp – sewn together by hand in the style of a loafer. They use only the finest leathers, vegetable tan them, and then treat them with olive oil.

They are very soft, and the natural leather together with the simple construction means they stretch and mould to the foot. For anyone that likes the feel of great leather, they are a pleasure.

I’ve been wearing La Portegna slippers for a while now, but I’ve always wanted a suede pair – because as you can probably imagine, they are even more soft and supple. My efforts to cajole José, the owner of La Portegna, into making some concluded last year with the idea of a Permanent Style collaboration – a one-off suede slipper, limited to 50 pairs and only available to PS readers.

We will be launching La Portegna x Permament Style – the perfect travel slipper – tomorrow. I hope you like it.

For more background on La Portegna, see my post from last year.

↧

↧

The perfect travel slipper

[See yesterday’s post for the story behind this collaboration]

These are the Permanent Style x La Portegnaslippers. In my experience the lightest, softest and most supple slippers available anywhere.

They are made from Spanish suede and handsewn by the lovely people at La Portegna. They roll up into the size of a fist. They are ideal for home, plane or hotel. (Though never outside – it is suede and it does get dirty!) I take mine in every weekend bag or suitcase I ever pack.

Fifty pairs of these slippers are available exclusively to Permanent Style readers over the next two weeks. La Portegna does not currently offer suede slippers, and it will never offer them again in this Permament Style purple.

The slippers cost €90. As with previous projects, the collaboration will work in the form of pre-orders, so that we only have to make as many as are desired – ensuring costs are kept down. After the offer has closed in two weeks’ time, Jose and his team will begin work and prepare the order. That should take around six weeks.

They are available in small (39-40 European), medium (41-42), large (43-44) and extra large (45-46). If you are between sizes (as I am) I recommend taking the size down; they are so soft that they will quickly stretch to your foot.

Orders should be made by emailing me: simon@simoncrompton.co.uk. If you have any questions, please use the comment section below so that others can benefit from the response.

Payment can be made by card, bank transaction or PayPal. Jose at La Portegna will contact people individually for payment once orders have been made. Postage and packing is €15 in Europe, €25 to the US and €45 elsewhere in the world. All other terms are as on the La Portegna site.

If previous Permanent Style projects are anything to go by, the slippers will sell out in the first few days, so I recommend ordering early.

If previous Permanent Style projects are anything to go by, the slippers will sell out in the first few days, so I recommend ordering early.

I hope you like them!

Simon

Simon

↧

Only two pairs left!

As I suspected, the travel slippers went very quickly yesterday and we now have only two pairs left out of the 50 available. First to email me gets them!

↧

Sold out!

Thanks everyone, all 50 pairs of slippers have now gone. Sorry to those who missed out.

↧

Reader question: belts with suits

I have been thinking lately about removing the belt loops from some of my bespoke suit trousers.

I was previously convinced that I wanted to remove the belt loops, but now I'm confused after discussing it with my Neapolitan tailor.

She is a proponent of belts. She argues that the Neapolitan custom, at least for 2 piece suits, is for belts. My recent survey of well-dressed men in Naples seems to confirm her view. Having visited Naples several times, what is your view on the custom for belts on a Neapolitan suit?

She also says she prefers the look of a nice leather belt to having only fabric at the waist, and argues that her casual cut lends itself more to belts than side adjusters, which are viewed as being more formal.

An additional problem is that there isn't enough fabric remaining in turn-ups to make side adjusters. Several of the suits are made from Smiths Whole Fleece, which has been depleted with no plans to be made again. Therefore, it doesn't seem possible to have side adjusters made, or at least not in the original cloth.

Given that I'm not a fan of braces, what would you suggest?

Many thanks

Andrew

-

Hi Andrew,

The Neapolitan standard is indeed for belts with suits, but not all Neapolitan tailors insist on it at all. I have a couple of pairs of trousers from Elia Caliendo with side adjustors, which work perfectly and suit both the cloth and the material. And of course Ambrosi also makes trousers without belt loops.

The preference towards belts in Naples is more a stylistic tendency that, perhaps, should make us all reconsider them. I certainly prefer side adjustors, particularly on a suit, but a leather belt can also be a thing of beauty.

I’m not sure I buy the argument that all Neapolitan suits are more casual and therefore go better with belts. A dark worsted suit, no matter how lightweight and flounced of shoulder, is still pretty formal. You could even argue that belts are unsuited to Naples because they are constricting, with the thick band of leather that much more noticeable in contrast to the lightweight suit.

But of course you undermine all this with your last point – that there isn’t enough cloth on the inside of the trousers anyway. You can have side adjustors made out of another material, but it would be a statement and one not easy to pull off. Certainly you don’t want it on many pairs of trousers.

So it sounds like you’re stuck with belt loops or braces.

↧

↧

Final panama hat from Brent Black

This is the Brent Black hat I had made last year and that a reader reminded me I had yet to report back on. I apologise, and can only plead a queue of other projects.

Back in August I wrote about Brent Black himself, the craftsman and campaigner, who lives and works in Hawaii.

His is the kind of business that makes me glad I live in the internet age. It is innovative, unswerving in its dedication to quality, and only possible because the internet allows Brent to connect directly with the few dozen customers around the world who are willing to pay for his uncompromising product. It allows him to bypass the economics of the rest of the industry, which have relentlessly undermined quality in favour of quantity.

I then wrote a post later that month about the hat-making process. In some ways it contains the best of all other crafts, requiring an involvement in everything from sourcing plant shoots fitting the human head.

Perhaps I am recapping these posts because there is relatively little to say about the finished hat. It is beautiful, perfect in every way. When it arrived it wasn’t perfect: it had a black hatband around it rather brown, as requested. But Brent went to extreme pains to correct that as swiftly as possible. And it is perfect now.

It is hopefully possible to see the fineness of the weave on the hat. I am not obsessive enough to count the number of rows per square inch, but I have never seen anything finer, including on hats that are a lot more expensive (this is Brent’s $1000 level of quality).

The fit is also a delight. As a man with a ‘long oval’ head, most hats do not fit very well until they have been reblocked to that shape, or worn enough times to adapt. Most felt hats will do that relatively quickly, but they are still never perfect, the brim always buckling slightly along the sides.

Even at the much cheaper end of Brent’s range (his hats start at around $500) I would recommend him for the impressive fit and dedication to the finished product.

↧

Cutler & Gross - interview with CEO Majid Mohammadi

I recently wrote a feature for the in-house Cutler & Gross magazine about the manufacturing of their glasses, including an interview with CEO Majid Mohammadi. It is reproduced below. C&G are in an interesting position, sitting between the very large, mass manufacturers and the smaller boutiques in Germany, Japan and the US.

Making our way home

As Cutler and Gross opens its London atelier, Simon Crompton considers the state of the eyewear industry and the enduring significance of craftsmanship and materials in the production of frames

Apparently, the latest thing in modern security equipment is smoke bombs; as soon as an alarm goes off, these devices fill the entire building with smoke. No one can see anything, so no one can steal anything. The intruders have little option but to stumble back the way they came and make a run for it.

Cutler and Gross’s new atelier in west London might seem like an odd place to be fitted with smoke bombs: two floors of a fairly anonymous building in Neasden occupied by a handful of designers, developers and engineers. There is some valuable glasses-making equipment, but that’s not the reason for the security. The really important things are the prototypes.

The new atelier opened in February this year and brings together the best elements of Cutler and Gross design. The first Cutler and Gross shop opened in Knightsbridge in 1969, and the Italian production facility was established in 2007.

‘Italians are wonderful craftsmen and they are obsessive about what they do,’ says Majid Mohammadi, CEO of Cutler and Gross, ‘though they’re perhaps not as passionate about management’. As an example, he recalls a moment during his career as a chartered accountant when he walked past a roomful of Italians having a meeting. ‘Everyone was screaming at each other, trying to make themselves heard. One guy was even standing on the table, stamping his foot, but no one was paying any attention.’

Majid values Italian craftsmen for their focus, which makes them great technicians. But London has arguably the brightest design minds in the world, so senior Italian staff will work in rotation at the London atelier, helping to bring practical solutions to the new design ideas their British colleagues are coming up with. Members of the London team will also visit Italy to learn more about how glasses are made.

‘That cross-pollination is crucial to a brand like ours, which needs to remain innovative yet produce wearable, timeless designs,’ says Majid. ‘Only when a designer sees the production process does he realise why certain things are made a certain way.’ Adding a fraction of a millimetre to the thickness of an arm, for example, can make a big difference to how well a frame wears over time.

The centrality of this production ethic is prominently illustrated on the staircase of the new atelier. Forty different frames are displayed up the stairs, each frozen after one of the forty stages involved in making a pair of Cutler and Gross glasses. So every time a designer goes to their desk, they will be reminded of the hand-polishing or the way the company logo is buried in the arm of a frame.

‘A direct connection to the item and the process is important,’ says Majid. ‘Often photography is too artistic, and distances you from the object. We want staff to feel an intimate relationship with the production.’ Ascending the stairs is also metaphorical – staff witness the gradual development of a Cutler and Gross frame from a rough piece of acetate into a work of art.

Stuck in the middle

Cutler and Gross is an oddball in the eyewear industry. Most producers fall into one of two camps: small artisans and mass producers. But Cutler and Gross is somewhere in between.

Every big fashion brand outsources the production – and often the design – of its glasses. Many turn to China and one of the big conglomerates like Luxottica, a manufacturer that takes some time and a decent amount of money coming up with a style, makes a mould and prints out hundreds of thousands of pairs.

Injection-moulded glasses can’t be heated and adjusted to fit in the same way that a handmade pair can be, and they will not be hand polished, so any scratches and scrapes cannot be buffed out; they are there to stay. Some very good glasses are made in China – indeed, some very good copies of Cutler and Gross designs are made in China (hence the prototype security protection at the new atelier). But fashion brands expect you to want a new pair in two years; they are not designed to last longer.

At the other end of the scale, there are still artisans in Italy, France and particularly Japan that hand make frames. They are unique and often highly original, but their small scale necessarily drives up their prices. Even with slightly larger companies, that remains a problem.

Although Cutler and Gross makes thousands of frames a year, this is nothing compared to the millions churned out for the mass market of trend-driven sunglasses. Each Cutler and Gross frame takes four weeks to make, and their individually crafted nature means there is a higher proportion of wastage. ‘When the hinges are screwed in by hand, part of the frame might be scratched. So then it has to go back to be polished again. You do that enough times and there will be a few that have to go in the bin,’ says Majid.

Perhaps more unusual than Cutler and Gross’s size is its Italian production. Until five years ago, the frames were made in several factories in France, Italy and Japan. Then the company took the opportunity to buy a bigger facility in Cadore, the ‘eyewear valley’ of Italy. ‘That was a game changer for us,’ says Majid. ‘It finally put everything in one place and enabled us to exert far greater control over the production.’

Control is a running theme at Cutler and Gross, which does its own photo shoots, marketing and – most unusually in the eyewear industry – distribution. Cutler and Gross never has sales; its customers understand the luxury market and buy into the price point that such exclusivity commands.

A big catalogue getting bigger

The archive of Cutler and Gross frames stands at over 1,000, multiplied by four when taking into account alternative colours and materials. A fraction of that is in constant production, while the vintage selection is available exclusively in Cutler and Gross shops and from the brand’s own website.

Startlingly for a company of their size, it will also readily make bespoke pairs, varying just the colour or the fundamental shape of the frame itself. As with many areas of Italian manufacturing such as suits and other menswear, this bespoke or made-to-measure service is enabled by the fact that all the glasses are created individually. There are plenty of Cutler and Gross customers who are prepared to invest in an exclusive design, and who will happily wait for their frames should certain materials need to be specially acquired.

The range of Cutler and Gross glasses will expand considerably with the innovations expected to come out of the new atelier. Precursors include models where two or three layers of acetate have been cut at different levels to leave a textured surface on the front of the frame. One example, which recreates part of a Piet Mondrian painting, shouts ‘rock star’.

Another creative development is the Precious Metal Collection, for which Cutler and Gross employs palladium and silver – as well as 18-carat gold, which gives an unexpectedly warm and luxurious feel to the frame. And, along with many others in the industry, the company is working with materials like titanium. ‘It’s all about quality though, that’s the important thing,’ says Majid. ‘Our normal steel is more expensive than the titanium most people use.’

He dismisses decorative options, like adding diamonds to a frame. ‘We want to do something more original, to push boundaries. Someone recently said that the reason they loved Cutler and Gross was because the brand is so strong; that if we were doing something, everyone would assume it was the best new thing. He said we could make glasses out of cork and everyone would follow. I don’t think we’ll ever go that far, but we certainly want to be innovative.’

With the potential for such game-changing innovation, perhaps smoke bombs are a sensible choice after all.

↧

Crafted: Makers of the exceptional

Sophie Coryndon's toolbox for her decorative lacquer pieces

These are good times for craft. Hermès is bringing its festival of artisans to London next month; Vacheron Constantin is touring Europe with a series of craft days; and this week saw the first exhibition held by Walpole’s Crafted programme.

Crafted was begun back in 2007 as a mentoring programme for small craftsmen – a little brother to Walpole’s more glamorous Brands of Tomorrow. Over the years it has grown into a badge of quality in the British luxury market, with strict criteria for size, integrity and skill. It has fostered friends of Permanent Style like Breanish Tweed, Fair Isle Knitwear and bespoke shoemakers Carreducker.

This is the first year an exhibition has been held of work by craftsmen that have been part of Crafted. And it was one of the most beautiful collections of objects I have ever seen.

Mr Smith's traditional British typography

Each exhibitor displayed some aspects of their craft, as well the end result. And so everywhere you had a startling contrast between rough, scarred tools and glittering product. The ancient wooden moulds used for crystal ware, which reminded me of hat moulds at Christy’s. Or the oily iron letterpress, which looked a close cousin to Northampton’s shoemaking machinery. And of course there were Carreducker’s rough wooden lasts.

Furniture maker, and bender, Angus Ross

The exhibition continues today and tomorrow, at Somerset House in London. It’s well worth a look.

↧

Things I was wrong about: The sleeveless cardigan

One of the disconcerting things about the growing popularity of Permanent Style is the regularity with which readers find old posts – usually via search engines – and question me about them. I dislike being called an expert today, whether it’s on questions on style, manufacture or fashion history, but I certainly know a lot more than when I started writing, over five years ago.

This is the first in an irregular series of posts on things that I got wrong. Or rather, more accurately, things about which I have changed my mind.

Almost exactly four years ago I wrote a post (Why sweaters cannot be stylish and practical) arguing that while the sleeveless cardigan was eminently practical in its colour, warmth and lack of bulk under a jacket, it could never be stylish worn on its own. The ordinary cardigan looks far better, I argued, but of course its sleeves make it less practical under a jacket.

The logic is faultless, but I think I was a little harsh on the sleeveless cardigan. It can, like many other items of classic style, appear a little fuddy-duddyish, but a little attention to how it is worn is all that is needed to avoid this association.

First, stick to dark, classic colours. Navy, as with any sweater, is the most versatile colour and should be bought first. After that, either a mid-grey or another dark colour such as bottle green.

Second, balance the rest of the outfit. If you are concerned about its associations, don’t wear a sleeveless cardigan with a tweed jacket and bow tie; try raw denim jeans and a washed cotton jacket instead.

And third, wear it to its greatest advantage: under a jacket. In this context it performs many of the same functions as a waistcoat, creating an attractive V on the chest and hiding the often messy area around the waistline. If you are not wearing a tie, it is one more much-needed piece in the ensemble. If darker than the jacket, it attractively shadows the line of the lapels.

I have three sleeveless cardigans, all from Drake’s, in navy, biscuit and cream. The navy is worn every week, usually with a jacket and jeans; the biscuit I like only under a suit but provides a nice accent to grey flannel; and the cream is worn even more rarely, but works best with a white shirt as a subtly alternate tone.

Oh, and always undo the top and bottom buttons. Even two at the top: it encourages a lazy flop in a tie that is consistently appealing.

↧

↧

How to buy... cycling clothing

The latest in my series for How to Spend Itis live. This time we look at cycling clothing, which inevitably focuses on Rapha and Timothy Everest's work with Brooks.

The series is intended to reveal the quality and construction behind items of menswear, and thus provide a more substantial shopping guide than that produced by most luxury magazines.

↧

Justin Fitzpatrick, the Shoe Snob, launches his shoes

A couple of weeks ago, Justin Fitzpatrick at The Shoe Snob launched his first range of shoes, which are now available at Gieves & Hawkes on Savile Row. For Justin, this is the culmination of a long period of working and dreaming.

He trained as a shoemaker with Stefano Bemer in Italy, before returning to the UK and setting up a shoeshine stand at Gieves, in order to earn cash while he worked on his own range of shoes. After two years of work and a lot of polishing, he finally has a shoe range to his name, J Fitzpatrick.

These are (for most people) mid-range shoes, priced between £300 and £350. They are Goodyear-welted, made in Spain and on bespoke lasts that Justin created himself – the most obvious return on his Bemer training and, more recently, work with Tony Gaziano. That bespoke touch gives them a little more shape through the arch and in the heel of the shoe.

Far more important, however, are the design and making aspects of Justin’s shoes. He has tried to include more complicated designs than you usually find for under £400, such as balmoral boots (pictured top), one-piece slip-ons (below) and ankle boots with detachable fringes (above). There are also more unusual touches, such as denim on the balmorals and double-sided monks.

On the construction side, the shoes have closed channels – so you can’t see the stitching on the sole of the shoe. This is one more process (it involves cutting a thin slice in the sole and then sticking it back over the stitching) and therefore adds to the cost.

I admire anyone launching their own business, and particularly someone working so hard towards it. Justin is now in Gieves all day now, so pop in and see the shoes.

You can see the full range here.

You can see the full range here.

↧

Chittleborough & Morgan suit: Part one

I recently began a suit project with Joe Morgan, one of the most supremely talented cutters on the Row.

Joe is both technically exacting and stylistically innovative. Not only does he make best use of the Tommy Nutter inheritance, updating those big lapels and nipped waist for a modern audience, but he continues to come up with new designs. Descending the stairs to the basement of 12 Savile Row will always reveal some new model, often inspired by one of the highly creative apprentices and tailors he works with, such as Michael Browne.

(Look out for a few of Michael’s outfits in the current issue of The Rake. He features in both the Pocket Guide and the blue-themed photo shoot. And Sarah Murray has a beautiful jacket to be featured in the magazine soon.)

My suit will be a navy three-piece, cut in a heavy twill from Dugdales with high-waisted trousers and a one-button jacket. We will incorporate many of the Nutters of Savile Row style points, but also some modern twists, such as lapped seams on the trousers. All grounded in that honest Huddersfield cloth.

As a precursor to the series, I include a few shots here of the trouser pattern Joe has made for me. It demonstrates a few of the technical points that translate into that particularly sharp cut that Joe is known for.

The first point to highlight is the left-hand side of the pattern above, which translates to the inside seam of the trouser. The fact that the gap between it and the pencil line is smaller at the top than the bottom shows that Joe cuts a relatively closed trouser, that is to hang perfectly when a man has his legs slightly closer together. Joe believes most tailors cut a trouser that is too open.

Second, the curve at the top of the other part of the trouser pattern shows what is called a ‘crooked seat’ – the angle required to get up and over my bum, and into the small of my back. Again, Joe thinks not enough tailors put that amount of slope into the pattern.

And the third point is a construction one. Joe does many things to shape the suit, relying less on the tailor to do so. The darting in the chest canvas, for example, is quite extreme, and in the image at the top of this post you can see how the waistband lining on the trousers is slit to allow it to curve.

There are plenty of others, such as making the top sleeve a lot bigger than the bottom sleeve, so the seam rotates inside the arm and can’t be seen from the front. But there’ll be plenty of time for those over the course of the series.

↧

Huddersfield’s mills and merchants explained

I was up in Yorkshire last week, based in Huddersfield and seeing a few of the mills and merchants, including Pennine, Johnsons and Dugdale.

Mills and cloth merchants are largely separate. The mill weaves the cloth, often for many different merchants and to their designs and specifications. So going around Pennine, for example, which is probably the highest quality mill in Yorkshire, you will see Dormeuil and Dugdale cloth being woven on the same looms. There is no difference in the weaving process, just the yarn that goes into it and the set of the weave.

Back to England, the remaining looming sheds weaving suitings in Yorkshire are:

What struck me hardest when I got back was the lack of understanding among bespoke customers, and even Savile Row tailors, about how the mills, the merchants and the various brands on the cloth books relate to each other. The front of house at one Row tailor thought Dugdale wove their own cloth, while most admitted they had never been up to see any of the processes – which leads to myths about the finishing, among other things.

Mills and cloth merchants are largely separate. The mill weaves the cloth, often for many different merchants and to their designs and specifications. So going around Pennine, for example, which is probably the highest quality mill in Yorkshire, you will see Dormeuil and Dugdale cloth being woven on the same looms. There is no difference in the weaving process, just the yarn that goes into it and the set of the weave.

There is then the finishing, which I will go into in a separate post. WT Johnson’s (below) and Holmfirth are the most significant fine worsted finishers remaining, though a re-vitalised Herbert Roberts is also improving.

The merchants perform a very important role. They come up with the designs, they hold the stock and they sell to the tailors (or indeed made-to-measure and RTW brands). They make big investments for gradual returns – it usually costs between £100,000 and £200,000 to lay down a bunch, with one or two ‘pieces’ (around 70m on average) being woven for each swatch.

In recent years, mills such as Taylor & Lodge have been putting out their own bunches, which confuses things slightly. Rather like how Bresciani or Drake’s have started selling their socks and ties directly to the customer, this muddies the waters slightly and creates some tensions in the industry. It’s even more complicated at shows such as Premier Vision, where someone like Gucci might be buying cloth from both mills and merchants.

Some merchants also own their own production. Scabal, for example, owns the Bower Roebuck mill, which then produces 99% for Scabal. And Holland & Sherry, which is now owned by the Tom James group of travelling tailors in the US, has a lot of its cloth woven by the Chilean mills that are also part of that US group. In fact, that organisation is entirely vertically integrated, from (Chilean) sheep to tailor.

Back to England, the remaining looming sheds weaving suitings in Yorkshire are:

- Pennine

- Bower Roebuck (owned by Scabal)

- Bulmer & Lumb (incorporating old mill names Taylor & Lodge, Arthur Harrison, Kaye & Stewart and Edwin Woodhouse)

- Gamma Beta (incorporating Hield and Moxon)

- Luxury Fabric (incorporating John Foster, William Halstead and Joshua Ellis

Merchants often weave with more than one mill – Dugdale’s uses three, for example.

And the major merchants with operations in the UK are:

- Holland & Sherry (owned by the US Tom James group)

- LBD Harrison’s (owned by the Dunsford family in Exeter)

- LBD bought Harrison’s a while ago, and also now owns the Lesser’s name and Porter & Harding

- Smith’s (only English merchant based in London)

- Owns W Bill

- Dugdale (only merchant still in the centre of Huddersfield)

- Owns Thomas Fisher and Duffin & Peace names

- Huddersfield Fine Worsteds (Owned by US distributors HMS)

- Owns Minnis, John G Hardy, Hunt & Winterbotham

- Brook Taverner

- Bateman & Ogden

- Scabal

- Dormeuil

One more complication: more progressive merchants often have a middle man between the merchant the mill, who is in charge of sourcing the yarn and arranging and managing the production. Someone like Dugdale has three individuals that do this specialising in different types of cloth. Dormeuil, on the other hand, has a separate company – Minova – that does it and is often confused for a mill itself.

I won’t get into the Italian mills, not least because I’ve only visited a couple, but generally they have their own brands (Cerruti, Barberis, Zegna), so there isn’t the English split between merchant and mill. They also weave for others (including many English merchants who still put ‘Made in England’ on their bunches) and have regional distributors (eg Dugdale distributes branded Cerruti cloth).

Photography: Luke Carby

↧

↧

Pennine Weavers, Yorkshire

As I mentioned in my previous post on Yorkshire mills and merchants, Pennine is one of the best independent mills left in the area. It is also the largest worsted weaver in the UK, with 32 Dornier looms, and weaves 30,000-35,000 metres a week (most for RTW). It reinvests at least 10% of its turnover every year, and recently bought only the second drawing-in machine in Europe – the first went to Cerruti in Italy.

Walking around the mill, you will see basic Super 80s twill on the same looms as Super 180s with cashmere. Finer cloth is generally woven slower, but otherwise there is no difference in the weaving process for these cloths. The difference is in the fineness (Super 100s number), the way the yarn is spun, the set of the weave (2x2, 2x1 and other factors) and then, elsewhere, the finishing.

Pennine weaves for most of the big merchants, including Dugdale and Holland & Sherry, and Dormeuil puts around 85% of its cloth through here. Interestingly, though, the trend in recent years has been for smaller and smaller lengths of cloth. Pennine’s minimum is only 15 metres, and Dormeuil recently put through an order of 40 sets of 15-metre lengths, for one particular customer.

“That kind of order would previously have been done by a single-width pattern maker, but there’s an increasing demand for quality in that part of the market,” says Gary Eastwook, Pennine’s director. “Two or three years ago we would have baulked at that order, because it’s so much more time and effort. But then we can do it and of course the price reflects the work required.”

Small lengths are disproportionately more work because the thing that takes the most time and manpower is not the weaving itself, but preparing the warp for each length and then drawing it in.

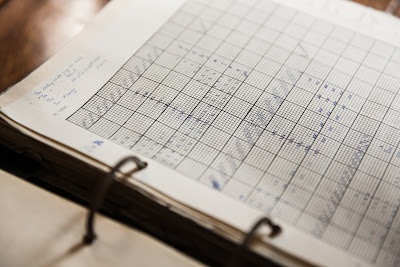

The warp is the yarn that runs the length of the cloth. To prepare it, precisely the right amount of yarn in each colour must be taken off cones, in the right order. Hundreds of ends over possibly hundreds of metres, all calculated on a yellow order sheet with graph-paper section showing the appropriate pattern (an old Dugdale pattern is pictured, top). Even a plain navy might have several different shades of blue in it, and black.

That warp is then transferred onto a beam that will sit at the back of the loom and feed it in, with the weft shuttling back and forth across it, coming from its own cones on either side of the loom.

[For more on weaving search for previous posts on Loro Piana and Breanish Tweed, the latter including a video of manual weaving.]

Luke Carby at work. Look out for his Pennine shots on The Rake's website

The warp must also be attached onto the loom, however, which is where the drawing-in machine comes in. Every end must be tied on. To do it by hand takes a day; the latest machine, which Pennine developed with Stäubli, does it in an hour.

Once everything is connected, the loom can start weaving. The only job required is for someone to tie on ends when the yarn breaks. Across Pennine’s 32 looms, that might happen every few minutes. The status of the looms can be monitored from a programme that also runs as an app on an iPad – so Gary can monitor them wherever he is.

A quick aside on weaving machinery: there is little benefit to older looms or older processes. If mills use old machinery, it’s because they can’t afford to buy new ones (they can cost up to £100,000). Old weavers, such as Fox, are gradually replacing their old looms and their flannel is no longer finished by bashing it against a wall (as we shall see in the next piece, on finishers WT Johnsons).

Perhaps the most impressive thing I saw at Pennine was the repairing of some Dormeuil cloth. One person was removing an errant navy thread (which I couldn’t see, even when it was pointed out) and replacing it with black. She tries to tie the new thread onto the old, and then pull it through the cloth. But the yarn often snaps because it is so fine. So she has to weave it in by hand, with the cloth containing perhaps 108 picks per inch. The whole process takes 10 days.

Yorkshire in April

↧

The Dugdale Brothers archives

One of the most interesting things about visiting Dugdale Brothers last week was their archives of order books, advertising and old products. The company goes back to 1896 and they still have the nicest premises of any merchant, going back to the 1920s and bang in the middle of Huddersfield. More on that next week. In the meantime, here are a few of my favourites from the archive books.

Dugdale used to sell all manner of accessories. It is still one of the few firms to still provide trimmings. Above, we have an advert for a clip that attached the shirt cuff to the sleeve of a suit jacket, so that a gentleman always showed the perfect amount of cuff. Still a market for that today?

Next, braces and shoe trees for boots

And finally, a series of brass buttons available with a range of flowers, admirals and prime ministers. And dogs.

↧

Reader question: Cashmere suits

Dear Simon,

Hello and congratulations on your blog's recent milestone!

I have a question regarding cashmere suits.

I am thinking of buying a suit that is 100% cashmere. Now I have come across many suits that are wool/cashmere blends, but not many that are 100% cashmere.

Is a suit that is completely cashmere practical? Will there be a lot of pilling, like there is with a cardigan for instance?

Thanks for your help.

Yours,

Farbod

-

Hi Farbod,

This touches on a question someone asked about ultra-fine wools on my post about Huddersfield mills last week. The finer a wool becomes, the more it loses body and elasticity; it loses some of the elements that make wool such a great material for clothing.

Cashmere is even worse. It is wonderfully soft, but this means it has very little body and memory. This can be OK in a jacket, which has internal structure in the chest to hold it together. But it is terrible in trousers. They have no chance of retaining a crease, and begin to bag at the knees after a while.

I know because I made that mistake with my first commission from Sartoria Vergallo. The jacket is great, but the trousers have lost shape very quickly. I still occasionally wear it as a suit, but mostly just as a jacket – it has patch pockets and brown horn buttons so works well in that regard.

I would avoid wool/cashmere mixes most of the time as well, at least for suits.

Simon

↧